Confession time: In high school, I owned a t-shirt that said Mrs. Darcy.

And I wore that shirt proudly to football games, Saturdays at the mall, and youth group. I was a unique teenager.

It all started in my Brit Lit class in my sophomore year. My teacher, Mr. Moore (who goes down in history as one of my favorites, and not just because of this anecdote) took to calling me Lizzy Bennet, maybe because of my rapier wit, but likely more to do with my resemblance to Jennifer Ehle of the Colin Firth miniseries. This likeness even fooled my Grammie June once, but that is another story for another day.

Serendipitously, I was taking this course the same year that the Keira Knightly adaptation hit the big screens, and we took an actual field trip to our independent cinema to view the film. I was never the same.

I connected deeply with all of Austen’s work, loving the passionate and reckless Marianne Dashwood of Sense & Sensibility, perhaps most of all. I drank up every piece of her writing, from her sarcastic juvenalia and the Gothic satire of Northanger Abbey to the revised ending of Persuasion and the unfinished Sanditon. I even found some love in my heart for Emma Woodhouse and Fanny Price of Mansfield Park. This love for Regency Era England expanded, but Austen was ever a favorite.

This spring, after an interlude of a couple of decades, I found Jane Austen again. Searching for a pleasant audiobook during these days of dissonance, I found Pride & Prejudice available on Libby. I was drawn right back into the story of Darcy and Elizabeth, and all the dangers of first impressions. Additionally, I was excessively diverted by the familiar passages, and I found myself quoting along with Mr. Bennet’s banter with his unknowing wife, Jane’s forbearing remarks, Lydia’s outrageous antics, and Mr. Collin’s ridiculous addresses. After this first foray back in Regency England, I continued wending down the lane with Sense & Sensibility, Persuasion, and Emma.

So if you are looking for book recommendations this month, I am steeped in Austen and nothing else. You will find nothing but Austenian heroines here this month, apologies if that isn’t your cuppa!

As I continued to rekindle friendships with such beloved characters, I was freshly taken by the sharpness of Austen’s signature wit and how—upon rereading—the affairs of the heart were less swoony and more sharp-study. Though Jane Austen's works often center on love and attachment, the characters refuse to put all hope in marriage. For instance, this quote from Sense & Sensibility.

“After all that is bewitching in the idea of a single and constant attachment, and all that can be said of one's happiness depending entirely on any particular person, it is not meant—it is not fit—it is not possible that it should be so.”

-Elinor Dashwood

Well said, Miss Dashwood.

Note: Though I am using some photos from film adaptations (that live rent-free in my head), rest assured: the source material is best.

I, for one, have always been a believer that Austen’s works are feminist in nature. The very idea of women as independent creatures was—at the time (and still can be)—revolutionary.

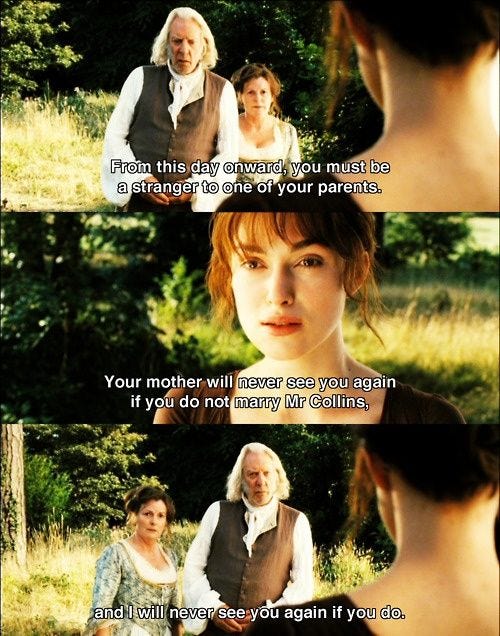

That Lizzy Bennet should deny Mr. Collins, a perfectly amiable—though wretchedly silly—match is outside of its time.

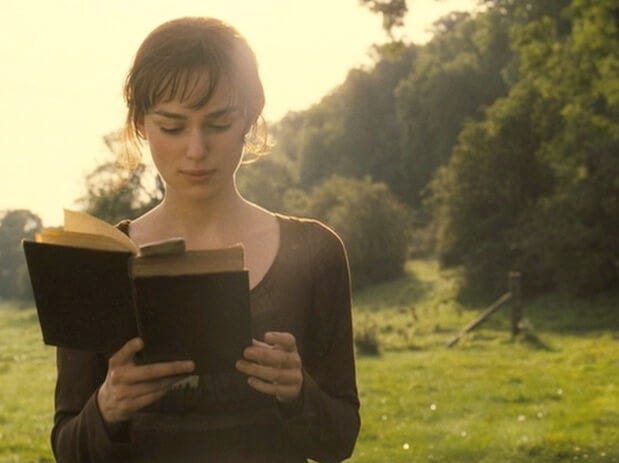

All five Bennet sisters have been given a sort of liberal independence in how they spend their time that would have been (and was to Lady Catherine De Bourgh) shocking at the time. But it seems that Lizzy and Mary are the only ones who enjoyed reading, and the latter seems to enjoy the moral posturing of it decidedly more than the occupation of it.

“And besides all this, she must have something more substantial, in the improvement of her mind by extensive reading."

-Mr. Darcy

That Marianne Dashwood cannot seem to disguise what she thinks in society of any kind is a type of freedom.

In fact, Marianne reminds me most of Virginia Woolf’s assertion in A Room of One’s Own, “Lock up your libraries if you like; but there is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.” Marianne will not be prevailed upon to change who she is or what she thinks, a quality that is as amiable as it is fiery.

Even in the novel’s title, Sense & Sensibility, readers at the time would have been likely a bit surprised that the paragon of sense in that novel is Elinor, the eldest Dashwood daughter

(note: a nerdy college RSM who was not ready to let Austen go wrote a paper about breaking down gender binaries with this very story at its center).

That Emma Woodhouse can declare that she has “very little intention of ever marrying at all” is perhaps the authoress herself speaking through the novel’s titular heroine. Though Emma breaks the mold of other Austen heroines, she is the one who stands to benefit the most from society’s status quo. She is a wealthy heiress with an invalid father, which ensures she can spend her days however she likes. With no want of fortune, consequence, or status, she is equal to many of the men (and considerably more than some) in the novel.

Thank you for joining me here for another month, dear readers!

Programming Note: I’m starting a new miniseries, attempting to answer the nearly impossible question,

“What is your favorite book?”

I plan to take some time over the next few months to unpack those favorites in no particular order (because ranking them would be out of the question).

I’ll add a Stack each month to my regular periodical schedule of current reads. So, dear readers, you can expect two Stacks a month for the next little bit. I’m hoping to follow the schedule below:

April - Modern fiction

May - Biography & memoir

June - On being a person in the world (Faith, embodiment, and more)

July - Canonical classics

August - Honorable mentions (some of my favorites that have stayed with me, and I hope will continue to do so)

I hope you will find some reads worth adding to your TBR list!

Cheers from my shelves to yours,

-RSM